Is U.S. law responsible for disinformation and misinformation posted on social media?

Find out what you think.

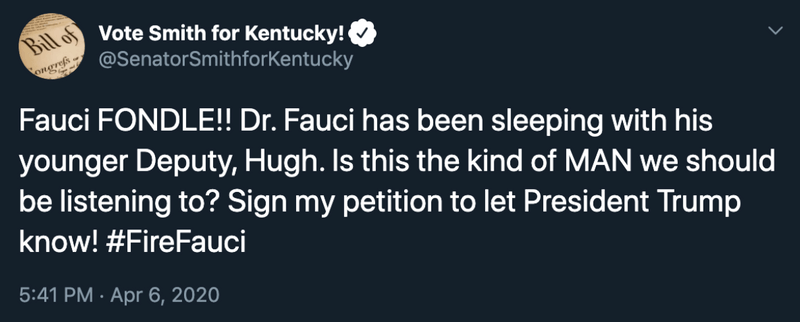

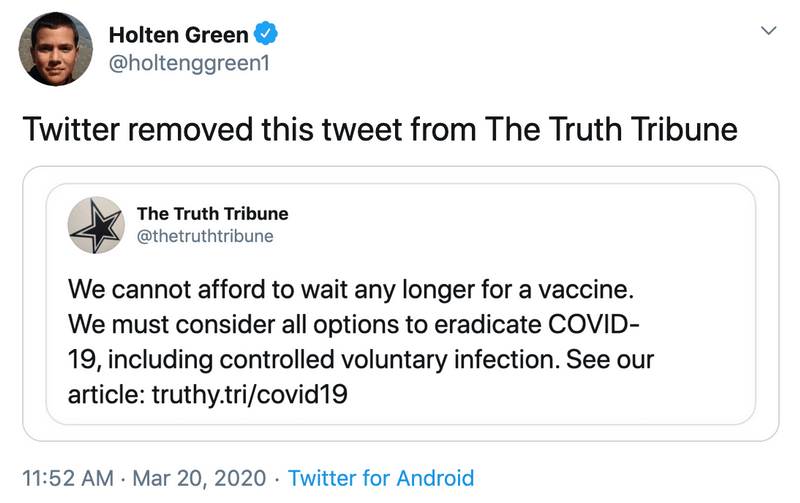

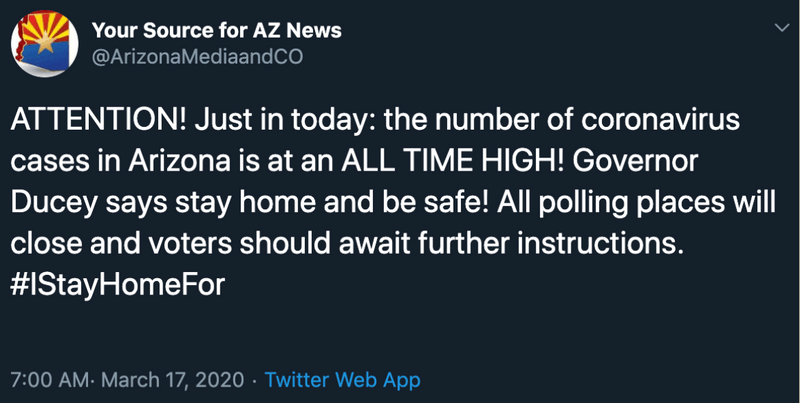

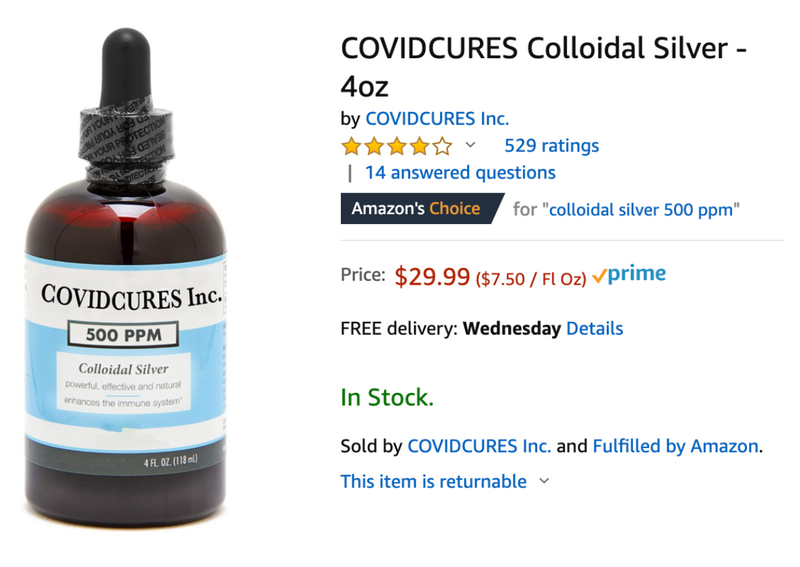

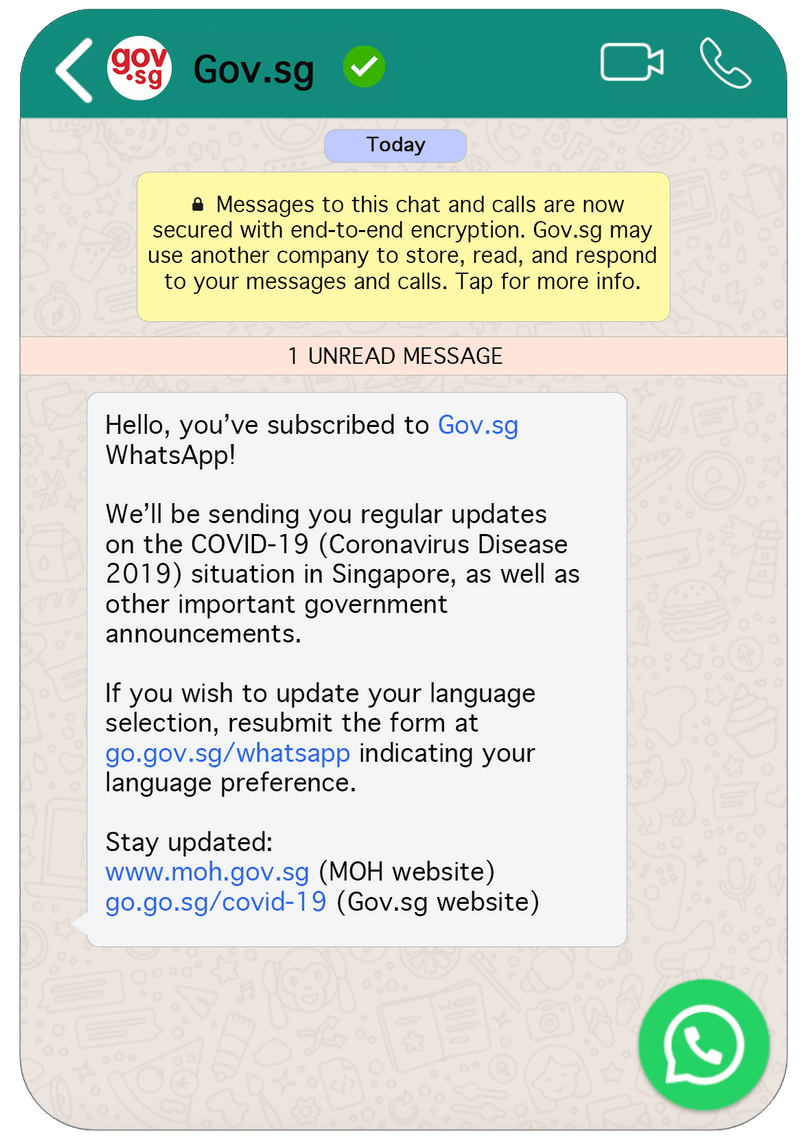

Recently, the Internet has been suffering from an “infodemic,” a crisis of misinformation and disinformation spreading faster than the COVID-19 pandemic. How should social media platforms deal with disinformation shared on their websites? Should the law require them to do anything? One particular law, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (“CDA 230”), affects the answer to this question.

This interactive tool will allow you to explore how the debate around CDA 230 relates to the dissemination of misinformation and disinformation today. Our quiz will help you develop an opinion about how CDA 230 impacts the moderation behavior and decisions of platforms.

Last updated: July 7th, 2020

For a more comprehensive view of CDA 230, check out this explainer or this guide.

This website is a project from the Assembly Student Fellowship of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. This site is currently evolving, and we are actively seeking feedback--please submit any comments here. This stuff is complicated, and involves precise language and subtle concepts -- we're working to make it both as accurate and accessible as can be as we hone our own understandings. And of course this should not be construed as legal advice.

Note: All of the posts used in this tool have been fabricated for educational purposes and should be considered within the context of answering only these questions. The user identities and handles are fictional and the posts’ content are not based on, nor intended to imply, any real-world developments.